This piece is the first in a series of articles examining Emily Dickinson’s life, work, legacy, and enduring significance in poetry and popular culture. Read the next part here.

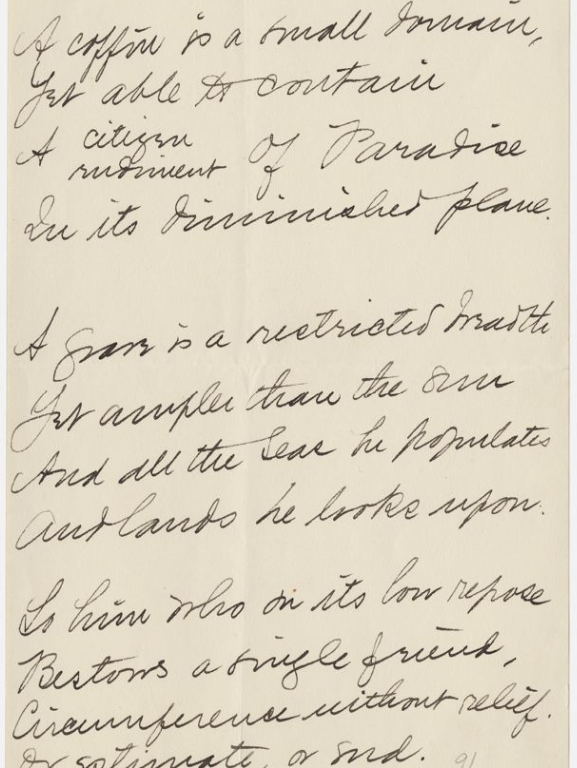

Emily Dickinson thought of death quite a bit. She wrote of it extensively too, with poems like “Because I could not stop for Death”, “I felt a funeral in my brain”, and “A coffin is a small domain”. Her words are punctuated by short phrases, idiosyncratic vocabulary, metaleptic punctuation, and vivid imagery, and her work is transcendental, of immense wit and intellect, capturing the zeitgeist of being a woman in the nineteenth century. Despite her ruminations on god, the nature of immortality and death, and ponderings on spirit and mind, she wrote with a refreshing verve and insight. Her words are a source of comfort today.

1.

“A Coffin — is a small Domain,

Yet able to contain

A Citizen of Paradise

In it diminished Plane.”

The trees of the West Cemetery in Amherst, Massachusetts sigh languidly on a lazy summer day as a gust of wind blows through their leaves. A feather rode the tides of the wind and swam through the air. The summertime haze lifted in the cemetery on Triangle Street and quickly, the feather frolicked its way through the gravestones and the trees. The day was strangely alive and the cemetery was occupied by a bunch of visitors across the 4-acre plot.

An iron fence separates some graves from the rest around which a throng of people stood. Miraculously, the feather swam above their heads, and just as sudden as the gust that had lifted it up originally, the wind died. The feather fell with a soft moan near the marble slab that was cool to touch in the balmy breeze, soft like a kiss. On it was engraved: “Emily Dickinson. Dec. 10, 1830. Called Back. May 15, 1886.”

The ground has memories, the soil remembers. May 19, 1886. It remembers the small funeral procession in the Dickinson Homestead. It remembers how the procession started at the parlor of the Homestead, then circled the poet’s flower garden and as per her own instructions, went through the house barn and through a grassy path lined with buttercups to the cemetery on Triangle Street. It remembers the beautiful white coffin and it remembers a grave lined with evergreen boughs laid by a loving heart and a trembling hand by Susan Gilbert Dickinson.

Emily Dickinson had breathed her last.

A small, yet intimate gallery of personas had gathered, who had loved this woman or seen her grow up. Austin and Susan Dickinson, her brother and sister-in-law held each other in their arms and watched her being lowered into the grave to begin the next great journey of existence. Susan would later write her obituary in The Springfield Republican, “A Damascus blade gleaming and glancing in the sun was her wit. Her swift poetic rapture was like the long glistening note of a bird one hears in the June woods at high noon, but can never see”.

2.

“A Grave — is a restricted Breadth —

Yet ampler than the Sun —

And all the Seas He populates

And Lands He looks upon”

Lavinia Dickinson, the youngest sibling, sat upright beside them, shaking. She had no inkling of the idea that she would find a vault of thousands of poems by her late sister later. Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Emily’s close friend and a fierce champion of her poetry was somber. He could not get the face of his friend out of his mind, sneaking a glance before they closed the coffin. He had read Emily Bronte’s poem, “No Coward Soul is Mine” at the service and smiled when he saw her lay peacefully in white clothes as if she slept.

He remembered the first words he ever read from her in a letter, “MR. HIGGINSON, — Are you too deeply occupied to say if my verse is alive?” It felt like that had been ages ago. He would later write, “E.D.’s face a wondrous restoration of youth – she is 54 [55] & looked 30, not a gray hair or wrinkle, & perfect peace on the beautiful brow. There was a little bunch of violets at the neck & one pink cypripedium; the sister Vinnie put in two heliotropes by her hand ‘to take to Judge Lord’.”

After Emily Dickinson was lowered into her eternal resting place in the earth’s loving embrace, a gravestone was erected with her initials, E.E.D. Years later, her niece, Martha Dickinson would change it to the white marble stone etched with the title of the Hugh Conway novel (“Called Back”), which still stands today.

3.

“There is not room for Death

Nor atom that his might could render void

Since thou art Being and Breath

And what thou art may never be destroyed.”

Emily Dickinson was a poet, a supposed recluse, an untethered free spirit. The woman in white. She wrote of immortality and legacy and hope, and yes, death. She wrote of funeral possessions and wild nights and bees and devotion. She was a revolutionary, a woman ahead of her own time, who wrote of her fears, aspirations, and beliefs with brazen honesty. Above everything else, she was loved.

She is laid to rest now in Amherst, Massachusetts, where she had lived all her life, with the rest of her family. Her words stay alive though, now more than ever. She did not see her words read by many before she passed, but her legacy endures.

Her life may have been short, but her words are eternal.

Acknowledgement: Each sub-section of this article begins with a verse from Emily Dickinson’s poem, “A Coffin is a Small Domain.”