Conrad Earp – Well, Saltzie, the thing is, I’d like to make a scene where all my characters are each gently, privately seduced into the deepest, dreamiest slumber of their lives as a result of their shared experience of a bewildering and bedazzling celestial mystery.

Saltzburg Keitel – A sleeping scene.

Conrad Earp – A scene of sleep.

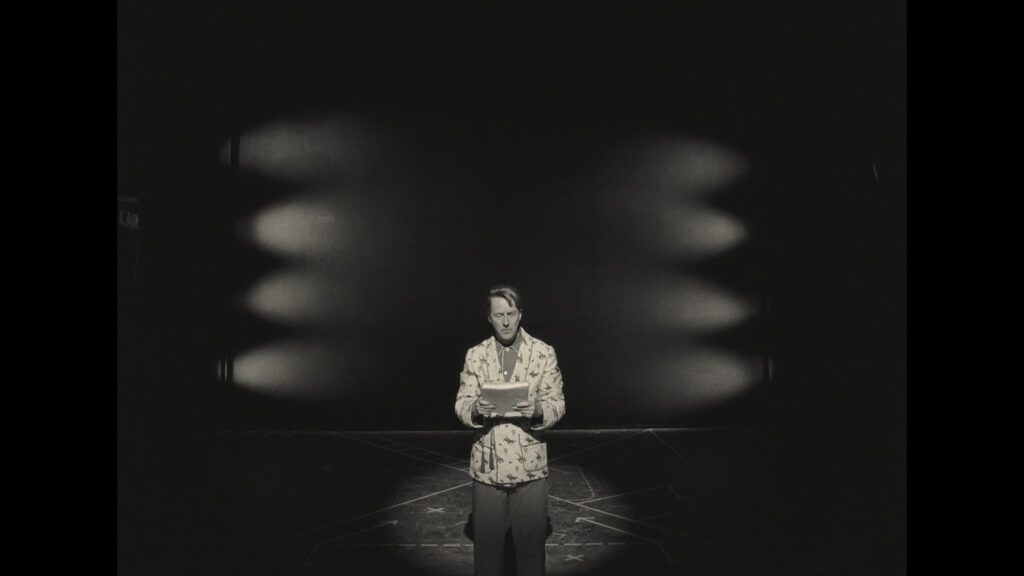

A scene in Wes Anderson’s Asteroid City sees Edward Norton’s Conrad Earp intone these words in a delicately measured rhythm, which are devoid of external emotion but are surprisingly, usually, profoundly expressive. Of course, it’s something Anderson’s characters are wont to do, in the signature long takes, unflinchingly gaze at the camera, or the audience: their words eloquent, yet deadpan. One can attest that bewilderingly, these words quite sum up what it is like to view this movie.

Asteroid City begins with Bryan Cranston’s narrator setting the scene. The movie we, the audience, see is actually a television special about the making of a modern American theatre production. Here, the actors are playing, well, actors, who themselves act out the segments of the play being produced. One obviously cannot not notice that the actors in real life are playing these aforementioned actors in the movie Asteroid City about a television special about… well, you know the drill.

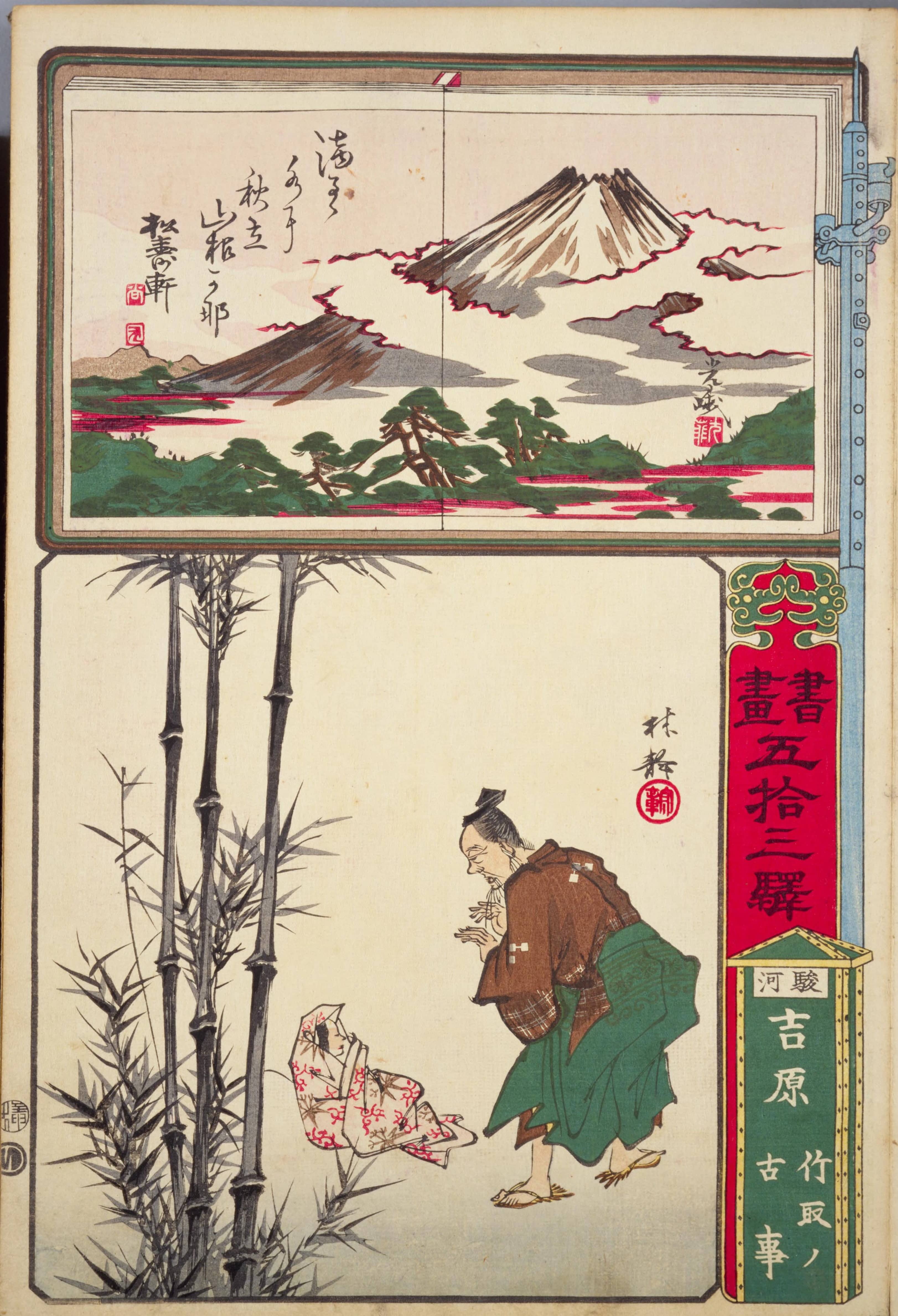

The main play, which the TV special is about, also called Asteroid City, is set somewhere in the Southern California-Nevada-Arizona desert and focuses on a stargazer convention, where different space cadets and their families are entangled with a young teacher leading a field trip to a bus full of elementary schoolchildren, a quirky motel manager, a singing cowboy, the US military, a socially awkward scientist and in a signature Anderson move, an actual alien.

The Densely Ambitious World of Asteroid City

This might be Anderson’s densest movie yet, not just in terms of the thematic juggernaut of ideas and emotions it can be about or is commenting on, but also in terms of the story and the characters. It’s also widely ambitious.

It is understandable why some viewers may find it less accessible. And yet somehow, it manages to reel you in. You might not even understand what the point of the movie was after all, but you are left with a gratifying sense of completion and an eager desire to come back for another round. From the moment Cranston appears on screen, you are captivated into this incredibly meta, sad, alive, bright, hilarious, zany, very, very Wes Anderson world as if privately seduced into the deepest, dreamiest slumber of your lives.

What is the movie about, then? Is it an exploration of how pandemic affected the society as a whole, or is it a tribute to Western movies and folksy music with a healthy dash of whimsy and sci-fi thrown in? Is it about moving on after the death of a loved one or is it about shared experiences with strangers leading you to a transformative journey?

Perhaps it is a satire on the space exploration frenzy and the American obsession with UFOs in the postwar 20th century, or perhaps it is a retrofuturistic story of lost souls in this universe trying to make sense of the experience of what it is to live or find meaning on a random floating piece of rock in the space when there appears to be none. It could very well be a love letter for the performing arts and the sweet labor that goes into it by those who create art, and then find ways to process and celebrate their experiences of existence as well as their trauma and joys and tribulations in life through their art.

Asteroid City could be about all of these or none. But what it is, for certain, is cinematic. It is not inaccessible, you just have to let your guard down and let yourself be swept into the slumber.

Augie Steenbeck and Existential Reflections

Augie Steenbeck: I still don’t understand the play.

Schubert Green: Doesn’t matter. Just keep telling the story.

Asteroid City in its very nature is profound and existential, or that is one way to interpret it. Jason Schwartzman’s gut-wrenchingly sincere portrayal of war photojournalist Augie Steenbeck is one of the many clear highlights in this movie. He’s also playing Jones Hall, the actor playing Steenbeck. Both roles have a common concordant theme: they are learning to cope with the loss of a loved one. His conversation with the director of the play, Schubert Green (played by the Anderson staple, Adrien Brody), about not understanding the play could just as easily be an allegory to a person mourning and struggling to live after an incidence of profound grief, as it could be about an actor attempting to make sense of complex emotions in his life through his art.

Another scene with Steenbeck involves a conversation with the cynical and depressed actress Midge Campbell (played by a marvelous Scarlett Johansson) about how he felt the alien looked at them as if they were doomed, to which she replies, “Maybe we are.”, could be about being comfortable with the fact that life may have no meaning as easily as it could also be about where her character is in terms of her personal journey. The takeaway is that Anderson doesn’t give any answers. It is on the viewers to interpret as they wish, and that is the beauty and frustration of Asteroid City. After all, we as viewers are playing multiple roles too.

We are watching the movie wherever we are watching it (a movie theatre, or on our laptops, tablets, or phones). We are also the viewers of the television special and the play the television special is about. Talk about breaking the non-existent fourth wall.

The Andersonian Touch

The signature Wes Anderson stamp is etched delightfully on the very fabric of this movie. The eccentric ensemble (filled with Anderson alums Jeffrey Wright, Tilda Swinton, Adrien Brody, Edward Norton, and a noticeably absent Bill Murray who could not participate in the filming due to a COVID infection and was replaced by an effusive Steve Carell), wide and satisfying camera angles, bright colors and an impeccable attention to detail, a Jarvis Cocker song (and a cameo too!), romance, precocious teenagers, world-weary adults, rock and folksy country and western music, prosaic and repetitive dialogue, panning shots of landscape and the characters, an overpowering sense of whimsy, all of it is packed symmetrically in this movie.

Anderson first-timers Scarlett Johansson, Tom Hanks, Steve Carrell, and Margot Robbie are given significant parts to toy around, with the latter appearing in just a single scene of massive thematic importance. A more challenging story on paper, the heartfelt acting, fantastic musical score, and beautiful vistas and visuals help penetrate the dense tapestry that makes this movie what it is and grounds it.

The Simple Complexity of Grief

Augie Steenback: When my father died, my mother told me, “He’s in the stars.” I told her, “The closest star, other than that one, is four and half light-years away with a surface temperature over 5,000 degrees centigrade.”

“He’s not in the stars,” I said. “He’s in the ground.”

She thought it would comfort me. She was an atheist.

One of the biggest takeaways from this movie for me was the utter simplicity of the message in one of the strangest sequences of the movie: the entire cast chanting “You can’t wake up if you don’t fall asleep.” in unison to the audience. As with any life experience, but particularly with processing grief, Augie says that “Time is maybe like a bandaid.”

It doesn’t heal your wounds, just covers them. Instead of numbing yourself to the overpowering woe of grief, one has to allow themselves to live through it. To feel whatever emotions the loss brings, in any way it does. Augie learns to do that in his own way both in and out of the play. One cannot overcome grief without having embraced it first. One cannot wake up until they fall asleep.

Wes Anderson is slowly cementing himself as one of the most prolific filmmakers and auteurs of this century, with his prolific style and a pedigree of genuine whimsical movies. While not as straightforward as The Grand Budapest Hotel, his latest entry in the form of a very existential and moving tribute to grief, southwestern America, extraterrestrials, and the very nature of art, Asteroid City is more than a worthy addition to his playbook of stylistic romps.

Asteroid City is for the outcast and the nerds, for anyone who feels like they could feel more at home outside Earth’s atmosphere. It is for the actors and the stage grips and the tech crew as much as it is for cowboys, conspiracy theorists, inventors, real estate investors, and believers in UFOs. It is for all those who fear that if they don’t make a sound, nobody will know they exist. It is for people in and out of love, and for those who have lost someone they loved.

The delicious absurdity in Asteroid City is in a way, quite like life. You do not understand all of it, but you enjoy it nevertheless. Or at least learn to.