Why live? Why go through the ordeal of life? Why travel paths filled with pain and suffering? It’s a dilemma humanity has faced and thought about, for centuries. Literature is replete with such conundrums, sometimes disguised as declarations, on the pointlessness of life and the inescapable tragedy of every moment.

There is but one serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide. Judging whether life is or is not worth living amounts to answering the fundamental question of philosophy.

Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus

There are more.

To be, or not to be, that is the question.

William Shakespeare, Hamlet

And more.

Is there any meaning in my life that the inevitable death awaiting me does not destroy?

Leo Tolstoy, My Confession

And many, many more.

One of the first signs of the beginning of understanding is the wish to die. This life appears unbearable, another unattainable. One is no longer ashamed of wanting to die; one asks to be moved from the old cell, which one hates, to a new one, which one will only in time come to hate.

Franz Kafka, Blue Octavo Notebooks

You get the idea, don’t you?

Care for a Challenge?

Long have I pondered over these thoughts too, an early quarter-life crisis ushered in by philosophers and authors who would fascinate and compel me to question the meaning behind any of it. Why wake up, why go through the same thing every day and hour and minute and second when you’re eventually going to die? Why go through the cycle of pain and suffering when it’s not going to bring you any feasible result in the end, only death and infinite oblivion? Why not embrace that earlier and skip through all the pain and suffering?

For any of my fellow readers who have wondered or still wonder the same question, let me try and persuade you to give The Tale of the Princess Kaguya a watch. The only motive with which I begin this argument is to show how this is one of the, if not the, greatest movies ever made, that the story is an assertive rebellion against Buddhist philosophy, a love letter to life itself, a story that finds meaning amongst meaninglessness. Not a tall order by any means, eh?

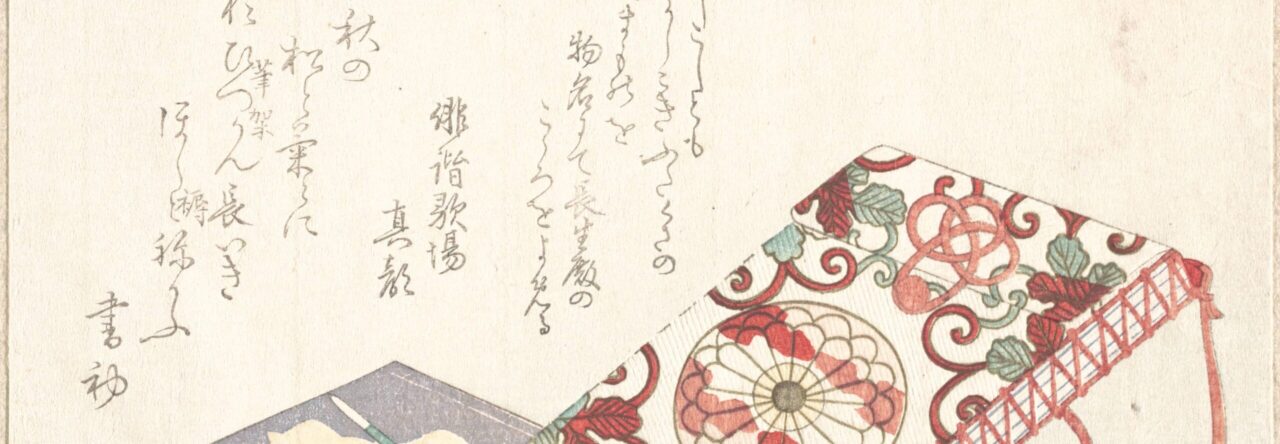

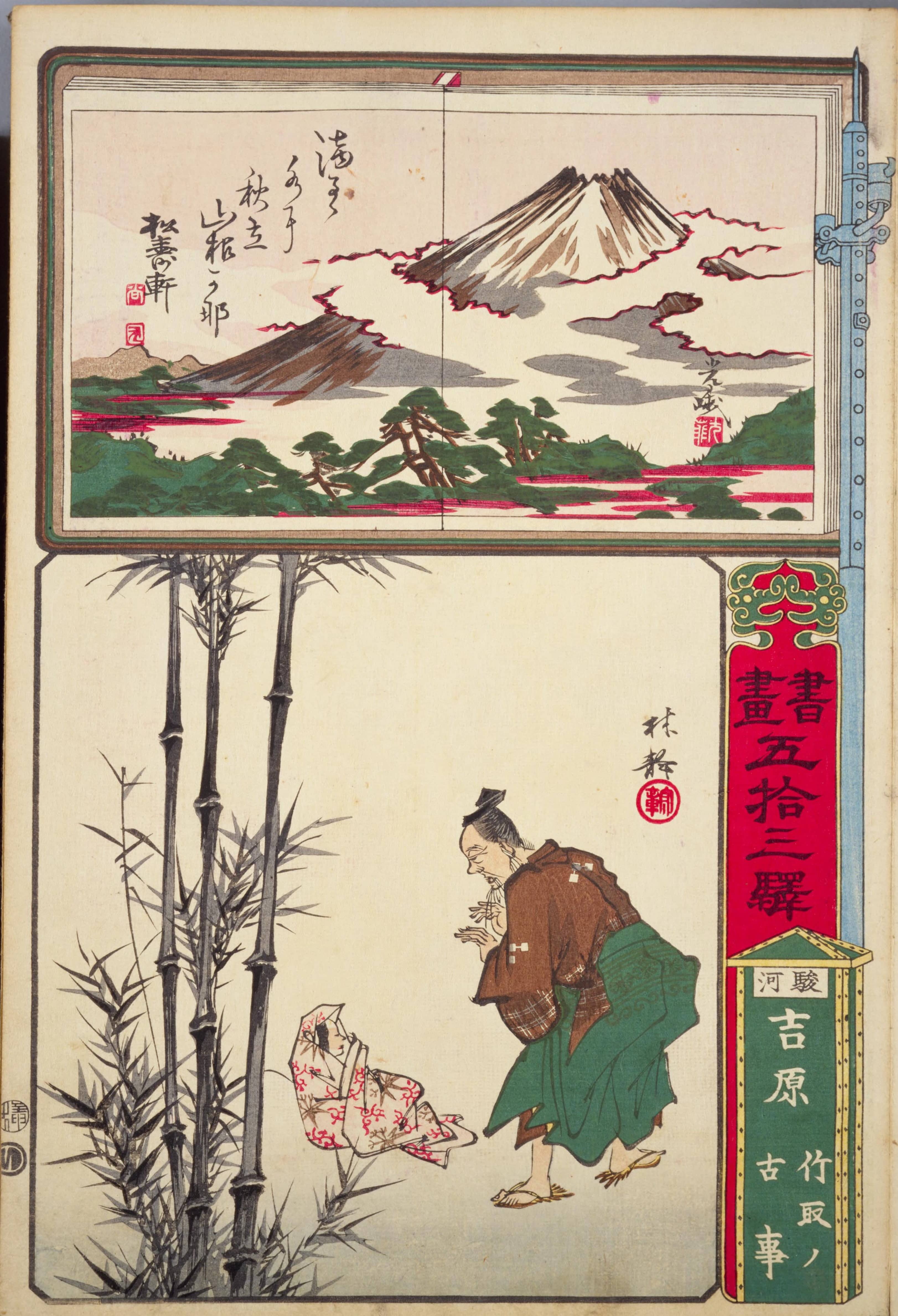

The Tale of the Bamboo-Cutter

It’s an old folk tale passed down over generations of Japanese families, of a princess who came from the Moon. Raised by a bamboo cutter and his wife, who found her inside a bamboo shoot, she grows to be an enchanting woman. Over time, the bamboo cutter would also find riches inside the same bamboo shoot, making him rich. As the princess grows up, stories of her captivating beauty would travel far and wide, resulting in different suitors coming and asking for her hand, only for her to set them nigh-impossible challenges to avoid marrying any one of them.

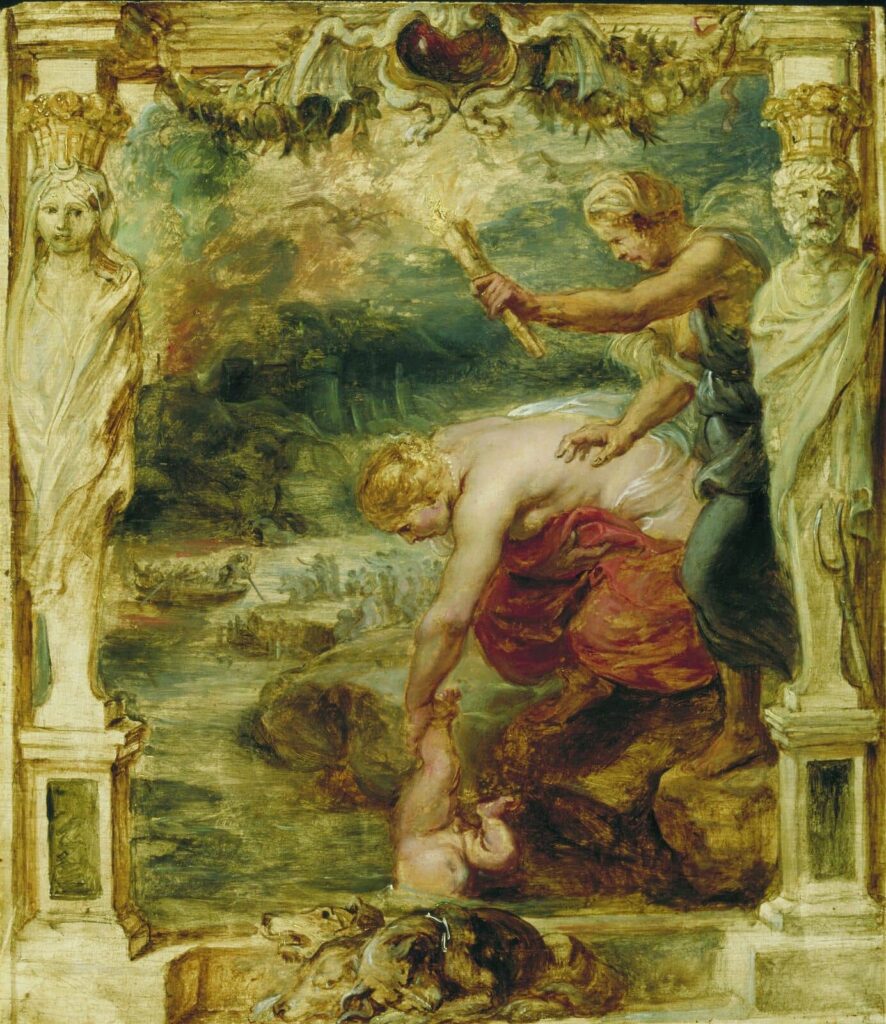

But the news of her existence would also reach the emperor, who would ask to see her. However, following her refusal, he visits her and immediately falls in love. When he tries to take her away, she threatens to disappear if forced. But soon, her time on Earth is over, and several heavenly beings would descend to carry her back to the Moon.

All of this is a well-known story, but it’s what Isao Takahata does with the folk tale that makes the ensuing piece truly magical. But before that, there’s some more info dump coming your way.

Buddhism and the Cycle of Rebirth

As per Buddhism, we’re all stuck in the cycle of samsara, or the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. It’s an endless cycle where you keep coming into a new existence every time you die, and in case you think it’s a good thing, ummm. It’s not. Life is a cesspool of suffering and misery and pain and as per Buddhist philosophies, the highest state of being you can attain is when you get beyond this cycle. Become free of this binding process.

It’s a concept that continually features across literature and philosophy, whether Eastern or Western (or Northern or Southern). Life is a pain in the ass, everyone unanimously echoes. Some of the optimists too. Not having a life is preferable to having one, everyone approves. That’s exactly why this movie creates such an impact. That’s exactly why this movie is what it is. It’s a love letter to the living despite showing the harshness that accompanies life on earth.

While the story in its original format isn’t so much of an elegy to life, the movie we’re talking about is. Very much so, and in the best way possible.

The Tale of the Princess Kaguya

It’s this little climactic conversation wherein the princess has to return to the moon with the celestial beings and Buddha himself (another change the movie opts for intentionally, I think) who’ve come to fetch her. A celestial being inches close, coaxing her to come with them:

In the purity of the City of the Moon, leave behind this world’s sorrow and uncleanness.

But the princess replies back, almost shouts, with utter indignation,

It’s not unclean! There’s joy, there’s grief. All who live here feel them in all their different shades! There’s birds, bugs, beasts, grass, trees, flowers… and feelings.

(The birds, bugs, beasts… line refers to traditional Japanese songs called Warabe Uta, something that frequently features in Takahata’s story, with a few modifications here and there.)

This. This is what lies at the heart of this magnum opus of a cinematic experience. The beauty in humanity, a fight against the cruel meaninglessness of existence. The meaning in emotions that surround you when you observe something larger than your definitions of beauty, something that suspends your time and space, leaves you in a daze. The meaning in love that you feel for someone, the sound of something sweet and tender, the taste of something hearty and delicious, the smell of something evocative and pleasant. Is that meaning not enough? Do those meanings not make it worth living?

It’s the little tweaks that Takahata adds to the story which incorporate new philosophical dimensions to the story, making it more interesting and complex. What if the princess wanted to come to earth instead of being sent? What if she missed her life even after her return to the moon (or death, as Takahata interprets it)?

All of a sudden, life becomes something to be desired, something to be yearned for, and that’s exactly what the movie does. Make you yearn for life.

The Coming Together of the Movie

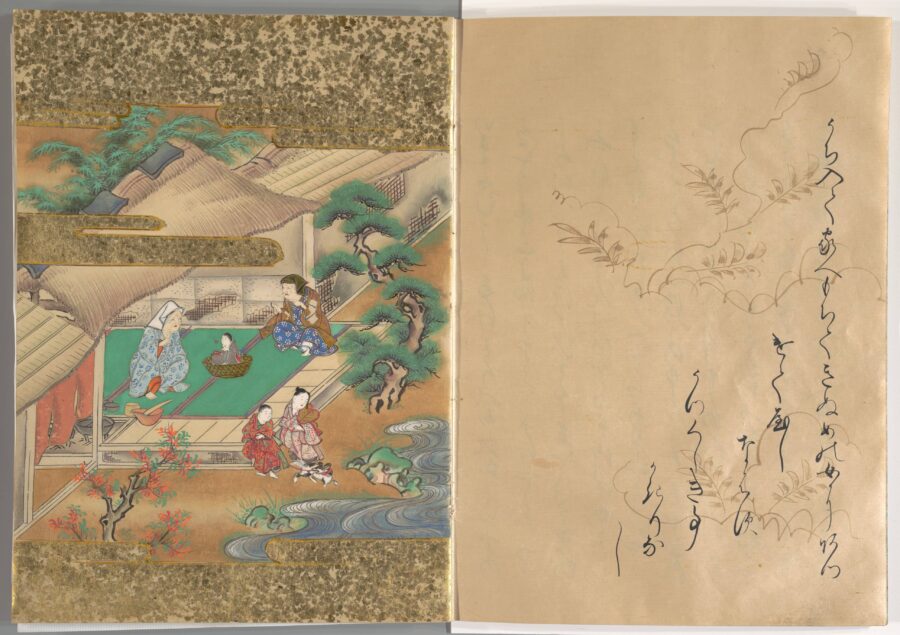

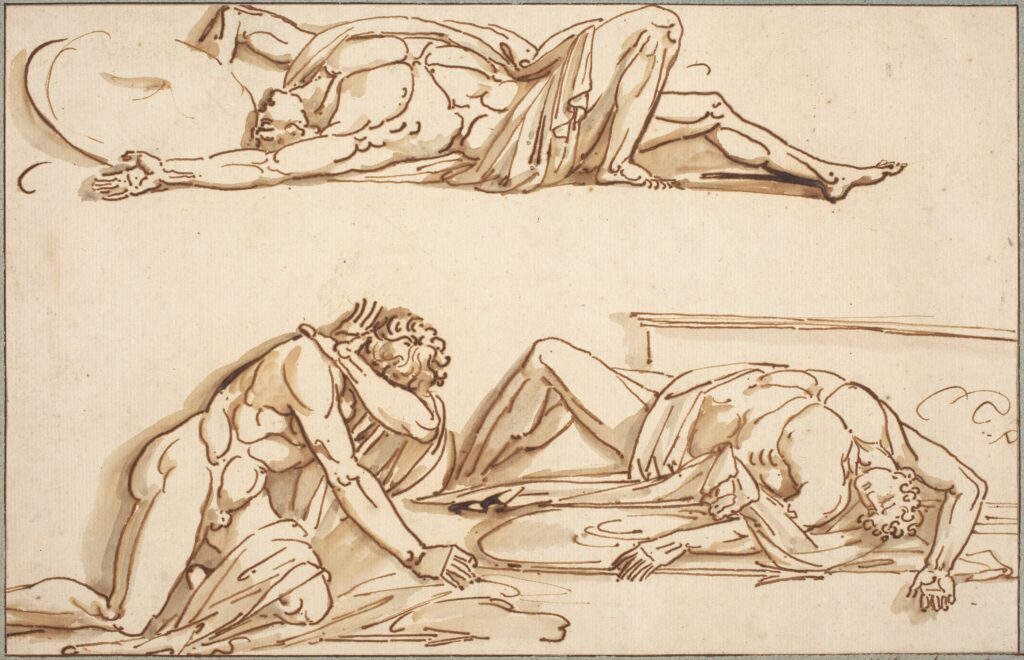

As is usually the case, it’s not just the final product that’s awe-inspiring. Consider creating a movie primarily using hand-sketched images, each painted with watercolors. Each painting giving the impression of a rough draft, creating a dream-like sequence from the beginning to the end, while also paying homage to the art form of the era this story is said to have originated from. (A rogue chain of thought makes me wonder if the rough sketches are meant to symbolize the rawness and simplicity of life itself.)

As you would expect, the enormity of carrying out something this difficult and complex was immense, why the movie would fail to meet deadlines one after another. The film will be postponed several times during its production, with many wondering if it’ll ever be brought to its conclusion. Takahata, in his search for perfection, went for the time-tested methodology of trial and error and eliminating the errors one at a time, until all that was left was, indeed, perfection.

From the music of the film (during and after watching Princess Kaguya, it’s hard not to wonder at times if you’re taking a mindfulness session, what with its serenity and tenderness) to the symbolic color changes (in one scene, the insides of the mouth go dark, to symbolize the feelings of the character while simultaneously highlighting the tone of the scene), everything reflects the hours and hours of thought and work that has gone behind it.

And what better way to create a movie on the beauty and meaning of life than creating it in a way that affirms your philosophy too? It’s a work that shows all that humanity can achieve when it puts its mind to something. In Isao Takahata and His Tale of Princess Kaguya, Yoshiaki Nishimura (one of the producers of the film) says:

“This is my movie,” I told Mr. Takahata.

He laughed and said, “You’re right. When everyone thinks it’s theirs, you get a good movie.” “I made this. The more people who think that, the better it’ll be.”

Sums up how this magnum opus was brought to life: everyone made it.

Final Thoughts

It’s too easy too often to get lost in the daily drudgery of life we have, in this modern world. It’s too easy too often to give in to the pain and suffering that is an inevitable part and parcel of our lives. But sometimes, just sometimes, admiring the petal, which has traveled through the wind, crossing who knows how many oceans, to fall at your feet, is enough. To take in the smell and touch of a fresh gust of wind that wants to embrace you. It’s enough. To laugh at the futility of it all, to chuckle at the beautiful absurdity that is our world. It’s enough. All that. Just that.

Or as Takahata would say, as long as you can answer back by being alive.