This piece is the second in a series of articles examining Emily Dickinson’s life, work, legacy, and enduring significance in poetry and popular culture. Read the first part here.

Lavinia Norcross Dickinson, or Vinnie, as she was fondly called, lived most of her life in the Dickinson Homestead in Amherst, Massachusetts, where she was born. Beautiful, loyal, curious, and vivacious, she devoted her time to housework and keeping the machine going. Of her, her niece, Martha Dickinson once wrote: “Upon her, very early, depended the real solidarity of the family”.

She had to, especially when her mother succumbed to grief after her father passed away in 1874. She never wed, and after her mother too had passed, she took care of her sister, Emily, a recluse who would one day make a name for herself in the world and leave behind a rich and enduring legacy of the Dickinson name.

Vinnie’s sister would one day rise up to become one of the most celebrated poets and one of the most exceptional minds of English literature. Emily Dickinson would one day take over the world with her words, even though she would not herself be around to see it. But it is a little-known fact, that the genius of Emily Dickinson might have not seen the light of day when it did, or at all, had it not been for sweet Vinnie.

An Extraordinary Poet & (not) a Recluse

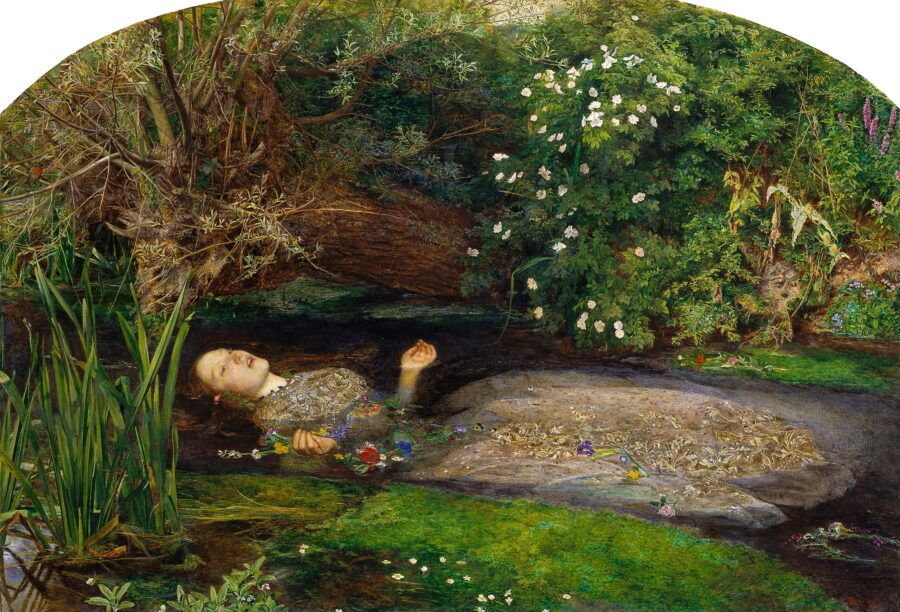

While Vinnie devotedly cooked and cleaned and kept the Homestead in order, her older sister Emily sat at her desk in her room and scribbled furiously as ideas poured out of her head in the form of exquisite poetry. While many misconstrue her as The Woman in White or a lonely woman, she had lived a full life.

She had correspondences with writers and poets, and a network of friends and family who supported her and loved her. She shared a special love with her sister-in-law, Susan Gilbert, wife to Austin Dickinson, who lived in the neighboring house, the Evergreens.

In one of her letters, she writes,

“To own a Susan of my own

Is of itself a Bliss –

Whatever Realm I forfeit, Lord,

Continue me in this!”

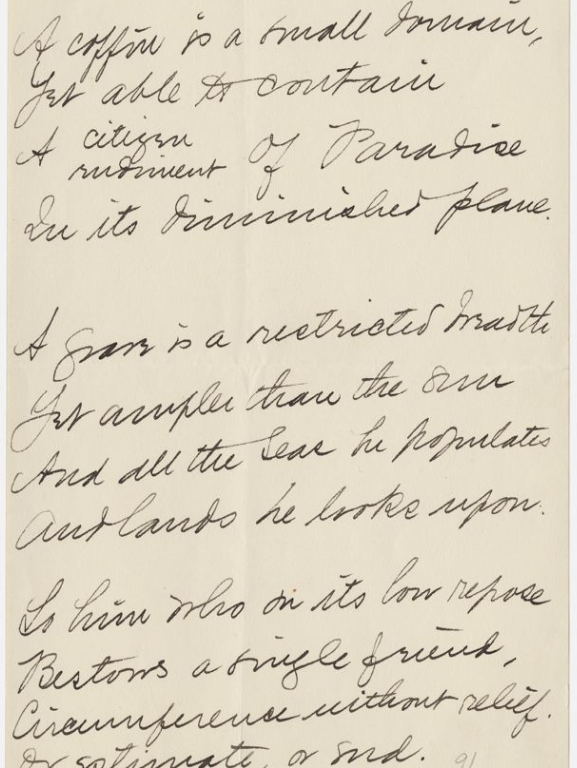

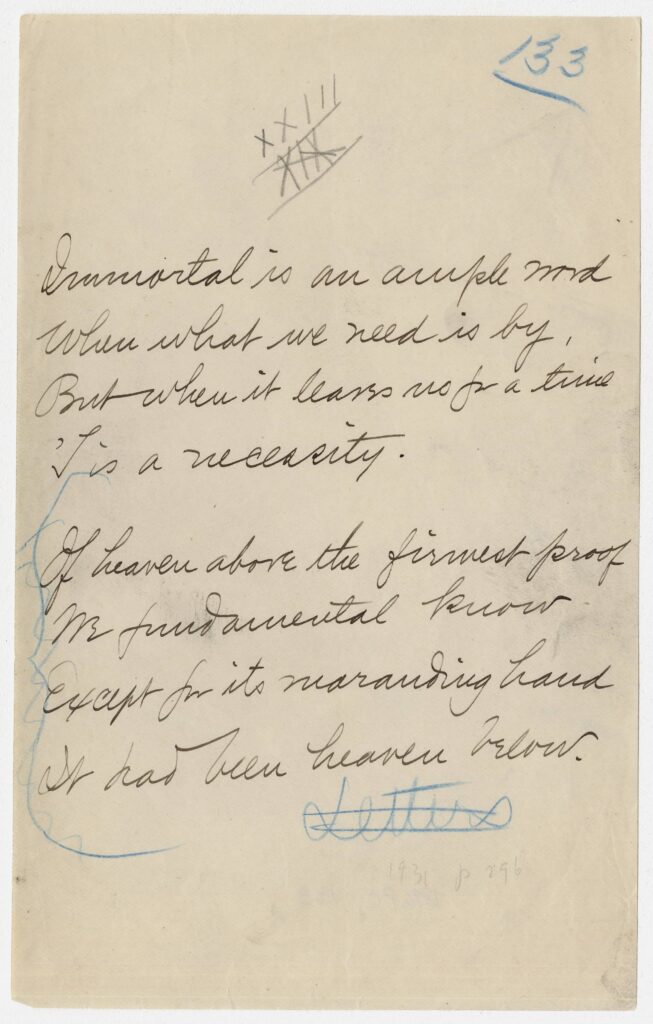

Emily wrote even when her eyes became weak and even when poor health grappled her sweet soul. Living a blissful solitary existence in her homestead, Emily wrote and she wrote until her fingers burned. In her last few years, she would rarely go out. Beset with a great number of personal tragedies and losses, and in helping Vinnie share the load of housework, her writing seemed to get more disorganized and frantic. She no longer collated her poetry in her booklets. She wrote on bits of paper, and she wrote on scraps, in a haste unlike any. She wrote until her health failed.

Before passing in the May of 1886 after more than two years of ill health, she requested Vinnie to burn her letters and correspondences.

The Chance Discovery of a Genius

Vinnie stood alone in the home she had known all her life, all alone, grieving for the loss of her sister who she had loved and protected all her life. She burned the letters and tried to make sense of the acute loss she had suffered in recent years. That is when she found them.

Now, Emily had been published before, anonymously and not, but not much of her work had reached beyond a certain few circles. Vinnie found hundreds of her sister’s poems, most of which were not read by eyes any other than Emily’s own. Her late sister had left no instructions as to what fate she wished for her words.

Vinnie took a decision. Her sister’s words would be published. The sheer brilliance of her work deserved its chance in the sun. Vinnie loved her sister. Within the next few years, Vinnie made all efforts conceivable to publish Emily’s work. She wasted no time in collecting her works and making sense of hundreds of scraps of paper her sister had left behind. She wrote to Thomas Wentworth Higginson, a revolutionary abolitionist, writer, and women’s rights movement supporter, Emily’s dear friend, frequent correspondent, and one of her staunchest supporters, in 1890: “I have had a ‘Joan of Arc’ feeling about Emilies poems from the first.”

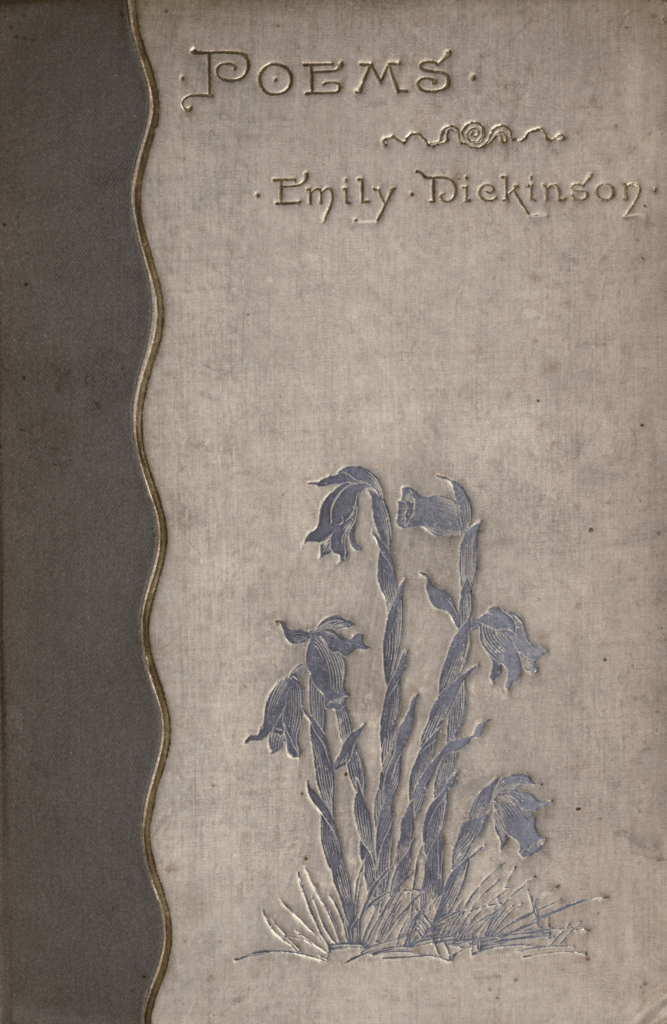

Due to her efforts, Higginson, who co-edited the first publication, and Mabel Loomis Todd, wife of an Amherst College professor and a celebrated artist, Poems of Emily Dickinson (the first series) was put to print in 1890, four years after the author had passed away.

Vinnie’s chest swelled with pride and she stood with her brother and Susan, her nephew and nieces, and Higginson and Todd. Poems though, did not even collect a small fraction of the material Emily had written over her lifetime. There was much work to be done. All of Dickinson’s work would not be collated until 1955, several editions later, when Thomas H. Johnson, a literary scholar would compile it all and edit the original manuscripts to publish The Poems of Emily Dickinson long after Vinnie and Higginson and Todd had all passed away. For now, tears streamed out of Vinnie’s determined eyes and she sat on the bed her sister slept on in the room her sister never left with a copy of Poems in her hand. This wasn’t the beginning, but it was a beginning. Emily Dickinson was well known enough in the town of Amherst, but soon, the entire world would know her sister’s name.